CHAPTER ONE

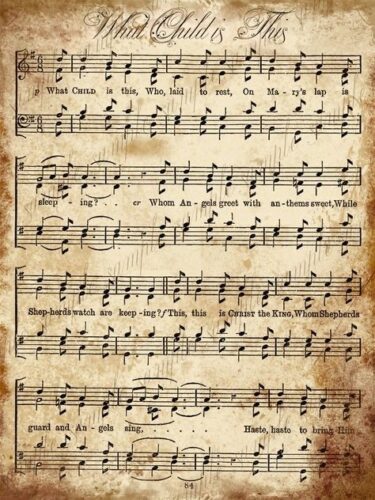

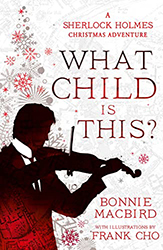

WHAT CHILD IS THIS?

This recognisable Christmas song, sung to the ancient tune of Greensleeves, has been a holiday favorite since Holmes’s time. Englishman William Chatterton Dix wrote the lyrics in 1865 and it was set to “Greensleeves”, a traditional English folk song, in 1871. There are over a thousand renditions of it on Spotify.

Try listening to this lovely Capella version here…

or for something quite different, you can listen to Andrea Bocelli and Mary Blige here.

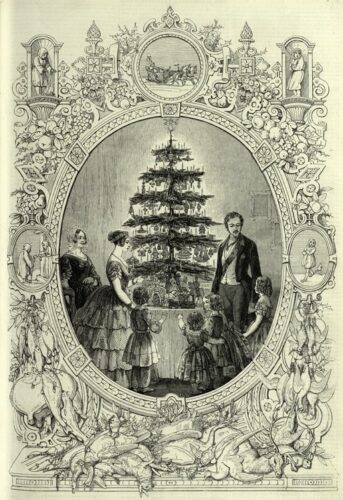

A VICTORIAN CHRISTMAS

From the Illustrated London News, Victoria and Albert in 1848

Most of the traditions we now follow for Christmas — the Christmas Tree, the red clad St. Nick or Santa Claus, Christmas Cards, and Christmas presents were popularised during Queen Victoria’s early reign. Her husband Albert brought many of these with him from Germany, they were embraced at the Palace, and adopted by the public gradually over the last half of the nineteenth century.

CHAPTER TWO

OXFORD STREET

A major thoroughfare in London, epicentre of Christmas shopping, then and now.

“in all directions are shops dear to the hearts of town and country ladies”—–The Queen’s London, 1896

Two photos from Holmes’s time:

And here, seen at a more recent Christmas time….

—Domiic Lipinski

A Tobacconist

When Watson and Holmes take refuge in the tobacconist’s shop it was likely very similar to this shop, James J Fox, on nearby St. James Street, which has sold smoking paraphernalia for 245 years. There’s even a museum downstairs. The store had many celebrated customers over the years including Oscar Wilde, and Winston Churchill. As Holmes was an expert on all kinds of tobacco and ash, he might very well have made his studies in this exact shop.

A lovely recreation of a Victorian tobacconists can be found at The Museum of London. Here’s a picture of it.

At this time only men commonly smoked in public but the ladies would occasionally indulge, in private. A very risqué practice. This photo is from 1890.

Gelatin silver print courtesy of Barbara Levine and Paige Ramey Collection, museum purchase funded by the Caroline Wiess Law Accessions Endowment Fund.

WHERE DID HOLMES KEEP HIS CIGARS?

A respectable gentleman might have kept his cigars in something like this elegant box.

Cigar humidor, nineteenth century “gothic revival” style

But respectability was not the watchword at 221B. In The Musgrave Ritual, Watson mentions that Holmes kept his tobacco in the toe of a Persian slipper, and his cigars in the coal scuttle. Here are three coal scuttles of the time, and no doubt the Havanas of this story found a temporary home in something like one of these.

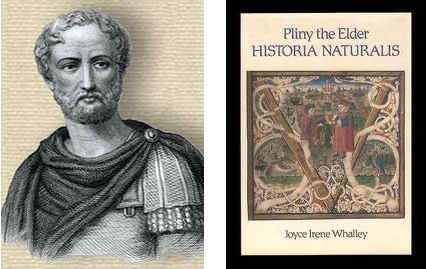

PLINY THE ELDER

Watson may misremember here, as the Natural History was several volumes in length. Perhaps he would prefer to forget as he found it hard going. But Pliny was noted as a scientist and a philosopher and his many pithy quotes resonate with us today. And we know that Holmes was fond of the pithy quote. Here are a few of Pliny’s.

“The only certainty is that nothing is certain.”

“An object in possession seldom retains the same charm it had in pursuit.”

“The depth of darkness to which you can descend and still live is an exact measure of the height to which you can aspire to reach.”

“True glory consists in doing what deserves to be written, in writing what deserves to be read.”

“In vino, veritas.” (In wine, there is truth).

“Home is where the heart is.”

Ready to take on Watson’s challenge? You can read Pliny’s natural history online at Project Gutenberg, here.

CHAPTER THREE

HORSERIDING IN TOWN

Rotten Row and the South Carriage Drive in Hyde Park at the time of our story, c.1890-1900, The Marquis of Blandbury would have been riding here.

Photomechanical print. Courtesy of Wikipedia.

Possibly he was wearing boots like these, while brandishing the crop as seen in the picture.

CHAPTER FOUR

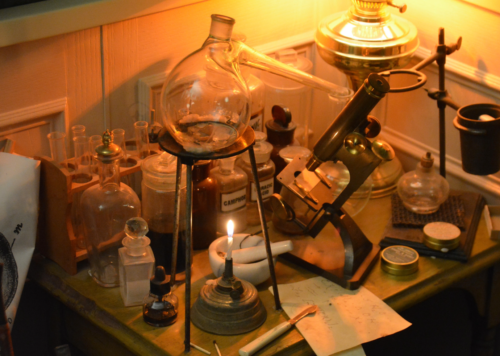

HOLMES’S CHEMISTRY TABLE

When little Jonathan has a near disaster at Holmes’s chemistry table, it might have looked something like this one in Dennis Dobry’s stunning recreation of 221B Baker Street in his home in Pennsylvania.

Recreation of 221b Baker Street in Reading, PA. View from window is also a reproduction. Photo by Robert Stek.

Or possibly like this in Chuck Kovacic’s wonderful 221B recreation in Los Angeles

Photo by Chuck Kovacek

CHAPTER FIVE

MAYFAIR

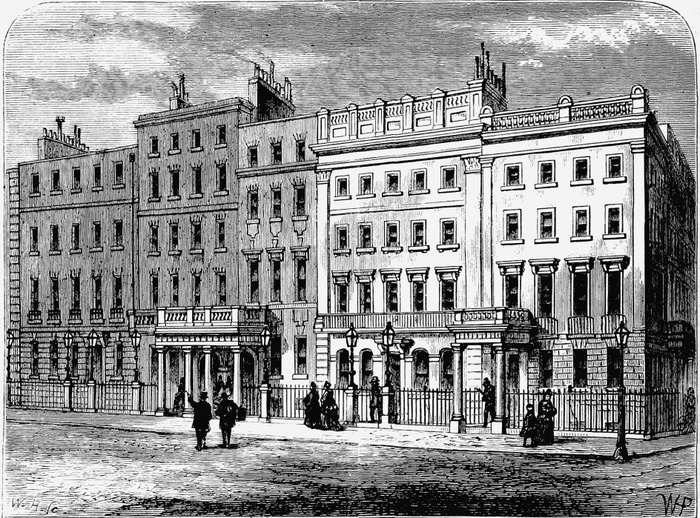

Mayfair was at the time one of the wealthiest areas of London and remains so to this day. To give you an idea of the frontages of the magnificent homes and buildings, on the left, is a Mayfair home recently listed for sale. The second image is a pen and ink illustration is of nearby Claridge’s.

Claridges (from here)

THE TREASURED VICTORIAN CHILD

Childcare for the upper classes was much romanticized in late Victorian times. This ad for Pears Soap is typical of the Victorian imagery on this subject.

January 1886, Hulton Archive.

In reality, though, in the aristocratic classes, the actual parents spent little time with their small children. Nurses and later tutors bore the brunt of childcare. Mrs. Endicott here is an exception.

Jonathan would have had many toys, such as the wooden blocks mentioned in the chapter, which might have looked like this exquisite German set of the time.

Victorian wooden block castle set, from Germany, as offered for sale on Etsy.

Hie might have had a rocking horse such as this Victorian example.

A Charming booklet about Victorian toys (including some you can make!) is here.

CHAPTER SIX

This Victorian diamond and coral necklace c1870 as listed on 1rst Dibs might be very like Lady Endicott’s beautiful adornment — which was remarked upon by Jean Vidocq, that wily flatterer.

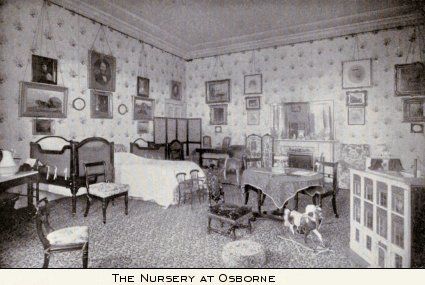

The intruder proceeded upstairs, and Holmes immediately intuited he was heading for the nursery. It might have looked something like this, though perhaps a little smaller, given it was in town.

A VICTORIAN NURSERY

SCULLERY MAID

The criminal who broke into the Endicott house tossed scalding water at the poor scullery maid. This position was usually held by a young girl, such as the one pictured here, and was the lowest rank of servants.

Scullery maids assisted the cook, keeping the fires lit and cleaning, cleaning, cleaning! It was a grueling job; she was often the first up in the morning and the last to bed. A tough life for a but perhaps one of the few options open to a poor girl or an orphan.

CHAPTER EIGHT

THE MARYLEBONE WORKHOUSE

Here’s the Marylebone workhouse at the time of our story.

And here is that same spot on Marylebone Road, now one of the campuses of the University of Westminster, just out the back window of the author.

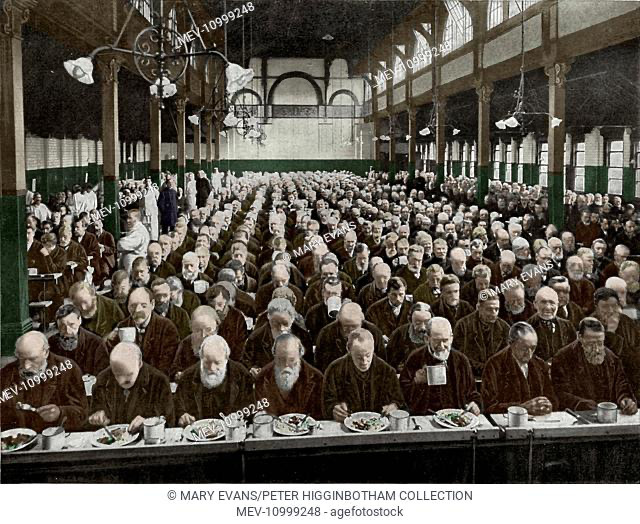

The Workhouse was a necessary evil and saved many from starving or freezing to death. But it was no luxury.

Upon entering the workhouse, one more or less gave up all rights. One’s clothes were taken and washed, then fumigated with sulphur. Couples were forcibly separated and the sexes remained apart throughout their stay.

Sleeping and eating were communal and highly regulated.

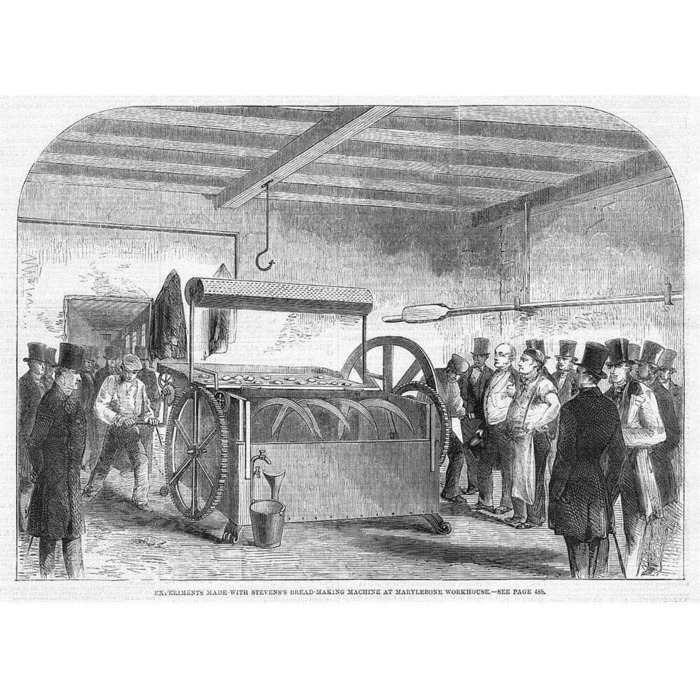

And one was put to work for long hours to justify or pay for one’s way. People picked oakum, scrubbed floors, worked in the laundry, the kitchen, the bakery, or other work stations.

This is a bread baking machine in the Marylebone Workhouse.

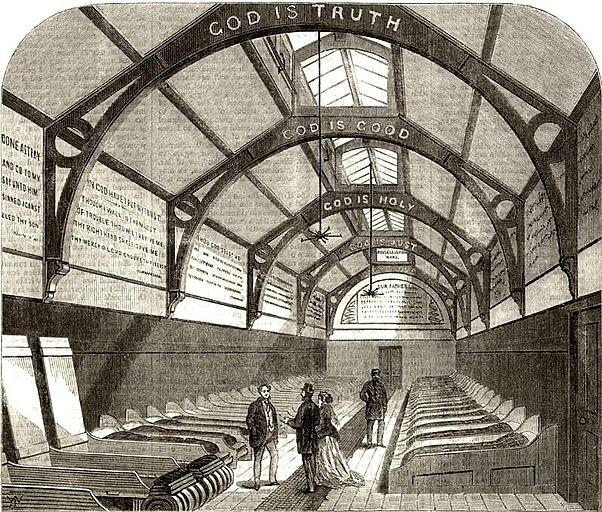

Religious sayings were everywhere, aiming to uplift but often feeling oppressive.

There was a nursery but it was a dangerous, cold environment for a small child. Many poor people chose to die on the streets rather than subject themselves to what felt like imprisonment for the e crime of merely being poor.

What Child is This?

What Child is This?